lesson 4a:

Portraits of Racially-Minoritised People

LESSON OBJECTIVES:

Upon completion of this lesson, students will be able to

1. Define elements of portraiture

2. Discuss how ideas of orientalism affect interpretation of portraits of racially-minoritised people.

3. Describe how art historians identify unnamed sitters in portraits.

What is a portrait?

A portrait, quite simply, is a painting that represents a person. However, portrait painting differs from (for example) taking a random photograph of a person, in that a portrait generally tries to represent something about the personality or life of that person. This could include having tools of the person’s trade (artist’s brushes, for example, or scientific instruments), symbols of the person’s wealth (furs or jewellery), or using expression (stern or smiling, for example) to indicate the personality of the sitter. Wealthy sitters often had more say over how they would be portrayed, and many portrait painters made money by flattering wealthy sitters. However, portraits can also tell something about the time period in which the painting was done, what was valued and what was acceptable.

“Portrait of Captain Thomas Lucy” by Godfrey Kneller, 1680; National Trust collection

Discussion: Take a look at the following portrait. What do you notice about it?

Orientalism and Portraiture

Orientalism is a 19th century movement in art where European and American artists fetishized the depictions of the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa. Paintings in this movement often depicted European/American fantasies around these regions, for example the paintings of harems in Morocco; however, they also depicted the fear of the unknown and the interest in travelling to these regions that Europeans and Americans had. While few went to the extremes of Frederick, Lord Leighton (whose house in Kensington is decorated in Syrian, Turkish and Egyptian tiles, textiles, and motifs), many wealthy artists and patrons of the arts had their portraits painted in Orientalist fashion to demonstrate their artistic taste and status. Lord Byron, for example, had a portrait painted in Albanian dress (Albania was then part of the Ottoman Empire) after he befriended Ali Pasha, the son of a local leader; and Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV of France and patron of the arts, had herself painted multiple times in Turkish costume.

Charles-André Van Loo, “Sultane” (portrait of Madame de Pompadour as a Sultana), 1747, original painting held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Writing Assignment: How does the portrait of Madame de Pompadour compare with the portrait of Captain Thomas Lucy? In what ways are both portraits similar? How are they different?

Black Portraiture

The Black people in Lucy’s and Pompadour’s paintings remain not only anonymous, but invisible in the titles of the paintings. This is very often the case when Black people are part of portraits or even when they are the subject of portraits. Peter Brathwaite, a Black British art historian (and opera singer) created a project during lockdown called Rediscovering Black Portraiture (Rediscovering Black Portraiture — Peter Brathwaite) and he wrote about looking for paintings of Black people:

“I assumed that the majority of paintings that I would find would be master-slave or master-servant type imagery, so I was surprised with my initial searches. However, once I exhausted that initial list I did encounter difficulties. This is when all of the other problematic aspects of representation within art, for example cataloguing, came to the forefront. It was often difficult to locate paintings, and often they were listed alongside derogatory terms – still – you’d be surprised by what I had to put into a search engine to locate some images. Frequently it was the case that the black sitters were not originally labelled at all, especially if they appeared in a painting with white sitters, regularly only that person was noted. It calls into question certain issues, how do we label art and talk about it? Moreover, how do we confront difficult histories, particularly against a backdrop of whitewashing?” (Rediscovering Black Portraiture - National Portrait Gallery)

Discussion: This portrait is unnamed. What can you tell about the sitter from the portrait?

Jan Jansz Mostaert, “Portrait of an African Man” (ca. 1525), painting in Rijksmuseum

Project on Black People in Art:

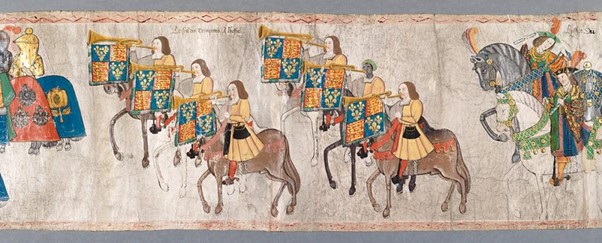

Students should choose one of the following pictures and discuss what the pictures can tell us, and research how historians discovered additional information or were able to identify the sitter.

Detail of 1511 Tournament Roll showing Black Trumpeter, held by the College of Arms

Mary Seacole by Albert Charles Challen, 1869 © National Portrait Gallery, London.