lesson 4:

The Pre-Raphaelite Rejection of Victorian Values

LESSON OBJECTIVES:

Upon completion of this lesson, students will be able to

1. Explain how the Pre-Raphaelite artists set themselves apart from traditional Victorian art

2. Indicate ways that the Pre-Raphaelites conformed to Victorian values

Who were the Pre-Raphaelites?

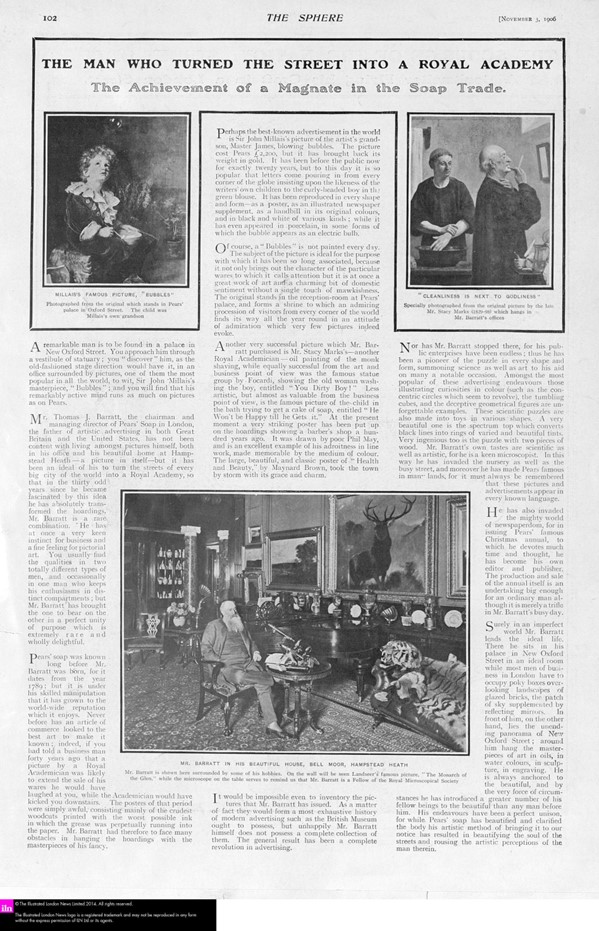

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in 1848 by British artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who wanted to return to ideals and methods of art used before the Italian painter Raphael (1483-1520). They rejected the British Royal Academy’s dominance of art and the sentimentality associated with popular art. An example of the kind of art that the Pre-Raphaelites abhorred is John Millais’s portrait of his grandson blowing bubbles, which was turned into a Pears’ Soap advertisement. Millais helped found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, but by the time he painted this painting he belonged to the Royal Academy.

Proof of advertisement for Pears Soap, adapted from a painting by Sir John Everett Millais, Bubbles, c. 1888 or 1889, color lithograph, 16.5 x 11.6 cm (V&A)

Discussion Question: Do you think Millais “sold out” by letting his painting be used in an advertisement?

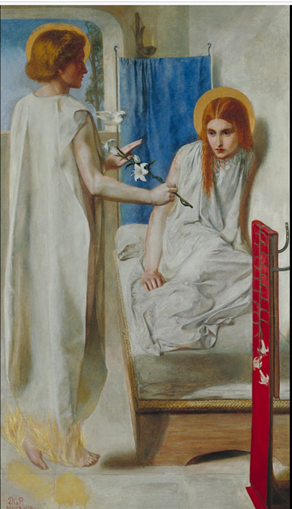

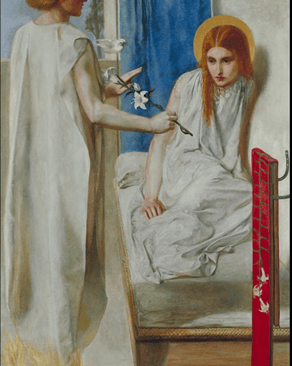

The Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti believed that Millais had betrayed their brotherhood’s artistic ideals. Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelites were “daring” by depicting working-class people, fallen women, and religious subjects without idealizing them. They thought art should be for and about ordinary people. In the two paintings below, we see evidence of the double standard of Victorian values around women’s sexuality. The middle-class man in Hunt’s portrait does not have to worry about his reputation, but his mistress does, which leads her to try to escape his clutches (see Why were the Pre-Raphaelites so shocking? | Tate). In Rossetti’s painting, a common subject (the announcement to Mary that she is pregnant with God’s child) is depicted in shocking form: Mary (who is red-haired, a colour often signifying bad temper or sexual indiscretion in Victorian literature and art) looks miserable rather than overjoyed at the news that the angel is bringing. This was seen in some circles as blasphemous, yet others found it refreshing and the Pre-Raphaelites took on many church commissions during their day.

William Holman Hunt, “The Awakening Conscience” 1853; painting held by Tate Britain. (above)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “Ecce Ancilla Domini! [The Anunciation]” 1849-50; painting held in Tate Britain. (right)

Quick Quiz: Which of the following is correct?

a. The Pre-Raphaelite artists painted rich people.

b. The Pre-Raphaelite artists painted Biblical figures as ordinary people.

c. The Pre-Raphaelites were banned from going to church because of their art.

The Pre-Raphaelites and Beauty

The Pre-Raphaelite painters had particular notions of female beauty. Many of their paintings include melancholy women with long, thick hair, and soulful eyes, dressed in free-flowing gowns. The loose hair and gowns countered strict Victorian propriety and dress codes, and thus were another way that the Pre-Raphaelites shocked society. However, these “stunners” (as Dante Gabriel Rossetti called them) often crossed other Victorian boundaries; many, like Lizzie Siddall, were working-class but came to the Pre-Raphaelites to be educated in artistic techniques (PRE-RAPHAELITE STUNNERS AND THEIR STORIES | Ashmolean Museum, Elizabeth Siddal - Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood). Some had artistic skills of their own, such as Jane Morris’s embroidery skills which she used to good purpose in making clothes in the style that would become the signature of the Pre-Raphaelite models. Christina Rossetti, who was herself the model for the Virgin Mary in Ecce Ancilla Domini, commented in her poem, “In An Artist’s Studio” (1896) that artists—presumably including her brother—treat models like something to be consumed: “He feeds upon her face by day and night”. Perhaps her work with the “fallen women” caused her to be concerned for her brother’s tendency to take his models as his lovers. But like Rossetti herself, many of these women were talented in their own right.

Art that takes in all the world

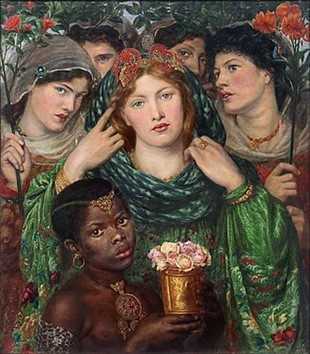

Although the Pre-Raphaelites were decidedly British artists, often depicting British literary scenes such as Arthurian legends or Shakespearean plays, they were also subjects of the British Empire. While many early 19th century painters had gone to places, particularly in the Middle East or Asia, where Britain had interests, the Pre-Raphaelites did not need to leave home to find a variety of models. One of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s most famous paintings is “The Beloved”, showing a bride surrounded by attendants going to meet her groom. The title is taken from the Biblical Song of Solomon.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “The Beloved” (aka “The Bride”), 1865-6, Tate Britain

All of the models in this painting were living in London when Rossetti asked them to model, and all but the boy in front, who Rossetti noticed at a nearby hotel, were regular models for the painting group. The model for the bride, Alexa Wilding, was a sixteen-year-old dressmaker’s trainee whose family was originally from Shropshire. To the right of the painting are two models who would have been considered foreigners at the time, even though one was born in Cambridgeshire. Keomi Gray, the only model not looking at the viewer, came from a Romani family. Behind her, with her face half-hidden, is Fanny Eaton, who was born in Jamaica but lived in London the majority of her life.

Discussion Question: How does “The Beloved” defy Victorian conventions of beauty? How does it conform to them? Compare the women in this painting to the women on Walter Crane’s map of Empire seen in the first lesson. How are the women in both pictures treated similarly and how are they treated differently?